A Change of Art: Thematic Shifts in Soviet Anti-Religious Posters Before and During the Cold War

St. Basil's Cathedral in Moscow circa 1980s. CeriC, 2015.

By John Salgado, Baylor University

The Soviet Union, unquestionably established by the end of 1922, took upon itself a new means of ideological warfare—one concerning not economics and politics, but faith and religion. The Marxist ideology on which much of Soviet socialism was based considered religion to be an enemy of the people. As the U.S.S.R. sought to establish itself on the world stage, it needed to quell any possible enemies within its borders. Thus, religious persecution rose, with arrests and destruction of religious institutes becoming frequent throughout the reign of the Soviet Union. One manner in which the Soviet Union attempted to combat supposedly anti-socialist religious thought was to annihilate it within citizens via propaganda posters—art pieces specifically created to instigate an anti-religious response from Soviet viewers. By simply examining early drafts of the “Decree of the Party of Workers and Peasants Central Committee's Plenary Session on the Issues of the Party Program's Paragraph Thirteen Violation and on the Organization of Anti-Religious Propaganda” from 1921, an endorsement of this method can be clearly seen. Paragraph three in the draft, when translated from its original Russian, commands those in the party to participate in “cultural and educational activities directed against religion and in outright anti-religious propaganda” (Decree). Following this decree, propaganda was quickly introduced to the public via various media, though one of the most famous and prolific methods was found in the form of posters.

Over time, these propaganda pieces evolved to maximize their impact on deconversion, as effectively encouraging the abandonment of religion was the goal of such posters. Artists were employed to spend many an hour drawing a cartoon against faith on large poster paper so that they could quickly be printed to sway the masses. To maximize efficiency, however, the subjects of these pieces underwent various changes throughout the decades. This metamorphic effect poses an important question: how did the content of Soviet anti-religious propaganda posters develop during the lifespan of the Soviet Union? An examination of the historical facts will make its journey known.

The central themes of Soviet anti-religious posters shifted throughout the Cold War according to shifts in the cultural sphere, or more specifically the sociopolitical concerns of the centralized socialist government. Within the propaganda medium, religion was originally depicted as no more than anti-communist evil, a force allied with the oppressing upper class whose sole purpose was encouraging hope in a life hereafter as opposed to addressing the socialist concerns of today. Churchmen were no more than shackles to restrain working-class members from revolting against their rulers. As time went on, however, this image of wicked clergymen shifted into a priesthood of hypocrisy. Accusations flew against clerics who seemingly lacked faith in the very spiritual remedies they pushed onto others. Finally, these images were swapped for a depiction of the faithful as foolish. Only a man in denial of science’s advancements would seek salvation through religion. For each one of these choices, the winds of culture governed their illustrators, with specific concerns of the Soviet government gripping propaganda works for generally twenty years at a time. Subjects were meticulously chosen to best relate to their audiences and were quickly slapped upon posters. Carefully planning such contents ensured the message could easily be plastered in the public sphere and would be understandable to the educated and the illiterate alike. The thematic choices behind Soviet anti-religious propaganda posters were governed by the ever-modernizing developments and climate of the U.S.S.R., so that each piece could best conform to its Patron’s concerns at the time.

Historiography

In the wake of the Soviet Union’s creation, a new battle was underway. This battle wasn’t necessarily one of weaponry and violence (though both would bleed into the discussion), but rather was a battle of belief—a struggle between an atheistic state and a religious people. The atheistic state, during the buildup and duration of the Cold War, attempted to suppress religion in a myriad of ways, believing that religion was inherently at odds with socialist ideals. Karl Marx, the economic philosopher whose ideology of Marxism greatly contributed to the establishment of the U.S.S.R., argued in his introduction to A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right that religion is “the opium of the people” (Marx). And so, a quest was set to remove this opium. A primary weapon with which the Soviet Union attempted to rid the nation of religion was visual propaganda, specifically posters. Posters lined the streets of Russia, each one standing to make a point against faith.

While an outsider may not view anti-religious propaganda as the most effective tool of a totalitarian socialist state that possesses the power to suppress dissenters, Soviet officials who feared that religion would prove fatal for the country believed it was a priority. Joan Delaney Grossman, in her article “Khrushchev's Anti-Religious Policy and the Campaign of 1954,” notes that there was a “stress on party responsibility for anti-religious propaganda” by the time Nikita Khrushchev took power (“Anti-Religious Policy” 375). The Communist Party of the Soviet Union came to approach anti-religious propaganda as a science, requiring precision in depiction and expertise in content. Grossman writes in “Leadership of Antireligious Propaganda in the Soviet Union” that Soviet propaganda began to draw “heavy reliance on scholarly research” (“Antireligious Propaganda” 216). Propaganda was a sophisticated tool for the Soviets, and so the state attempted to perfect it.

Soviet anti-religious propaganda was not focused on creating a new belief system in its audience. Andrew Denny argues in his article “Soviet Propaganda” that traditional propaganda “may be defined as a concerted group effort to spread a particular belief or doctrine” (Denny 259). However, the totalitarian rule of the Soviet Union was not interested in instilling a replacement religion. Rather, the U.S.S.R. was more focused on simply suppressing and eventually ridding its citizens of religious beliefs. Thus, Denny argues that instead of brainwashing, Soviet anti-religious propaganda is a “means to rule the masses and is effected through appropriate regimentation of thought and consciousness” (Denny 259). Soviet propaganda was therefore more akin to a leash than a steering wheel. The beliefs of the Soviet people were to be kept within permissible boundaries of non-expression, as opposed to necessarily being replaced with atheism. Atheism was the final goal and dream of the Party, but the job of Soviet propaganda was to discourage religion, not replace it. So long as religion proliferated in the Soviet Union, the first step towards ideological freedom could not be considered complete.

In this context, another factor to note in understanding Soviet anti-religious propaganda is its perceived failure. The Soviet Union's perceptions of the success of its anti-religious campaignsare questionable, which in turn promoted adjustments to campaign approaches over time. David Powell states in “The Effectiveness of Soviet Anti-Religious Propaganda” that “how effective the Party has been in its effort to eliminate religion is clouded by uncertainty” due to a lack of statistics on religious believers in the Soviet Union (Powell 366). This statement from Powell is significant because it refers to the ambiguous nature of the propaganda’s success. It raises the question of whether the proliferation of religion in the region should be attributed to religious resilience or flaws in the Soviets’ approach to propaganda. For the purposes of this paper, the answer to this question is not relevant; rather, it is important to understand what the Soviets perceived to have caused the ongoing practice of religion in the U.S.S.R. Powell states that during the Cold War, it was largely believed that the Soviets’ propaganda primarily failed because the propaganda’s content “leaves much to be desired” and was wrought with “vulgar accusations” (Powell 373, 374). In other words, the propaganda seemingly failed to effectively transmit Soviet intentions for an ideological replacement, and often came across as no less than insulting to the audiences it was attempting to sway. The idea that Soviet propaganda was a failure, specifically in its prose throughout the Soviet Union’s reign, is key to answering questions regarding the development of Soviet anti-religious propaganda posters. These developments may have stemmed from redirections in their approaches to combat perceived failure.

Since Soviet anti-religious propaganda was of great importance for the state, it follows that propaganda posters presented to the public were frequently updated to depict the latest cultural shock, especially since social research had been poured into the creation of such pieces. Each poster was specifically designed with the intent of discouraging religious belief, and at times, the Soviets believed that such propaganda was failing at its job. When it did fail, the Soviets did not let go of this passion project of theirs, but reconducted their research and went back to the literal drawing board. This understanding regarding the importance of propaganda, as well as propaganda’s motivations for change due to failures in obtaining its goals, is the necessary groundwork for identifying how the content of Soviet anti-religious propaganda developed during and throughout the Cold War. The intent behind each work is important for comprehending the social chameleon that is Soviet propaganda. This paper will examine how it has changed, specifically backing the argument that propaganda shifted from a focus on clergy-capitalist alignment to priesthood hypocrisy to the foolishness of faith. Thus, this historiography builds a foundation for the following contents of this paper, which will in turn provide reasons why understanding the importance of propaganda to the Soviets and their views on its success are relevant fields of study, especially when tracing the developmental history of their propaganda posters.

An Age of Soviet Propaganda for the Suffering Proletariat

Coming out of the Russian Revolution, the new state required a means of assuaging the public. The recent overthrow of the former government left the people of Russia and its neighboring states concerned. Those skeptical of the newly rising European power required convincing to support the new socialist government. It wasn’t long before the Soviet Union, in an assertion of its moral standing alongside its people, began introducing propaganda posters that played off fear tactics to win supporters. John Curtiss and Alex Inkeles note in their article “Marxism in the U.S.S.R.—The Recent Revival” that by 1925, three years after Stalin’s rise to power in the Soviet Union, it became widely apparent to the Soviet government that it was necessary to “secure the socialist state from the danger of intervention and the attempted restoration of capitalism” (Curtiss and Inkeles 349). As such, Soviet illustrators attempted to paint those whom they deemed enemies as friends of capitalism. When it came to turning the Soviet populace against religion, posters quickly appeared throughout the state displaying the Russian Orthodox priesthood (alongside leaders of other religions) in conspiracy with capitalist enemies.

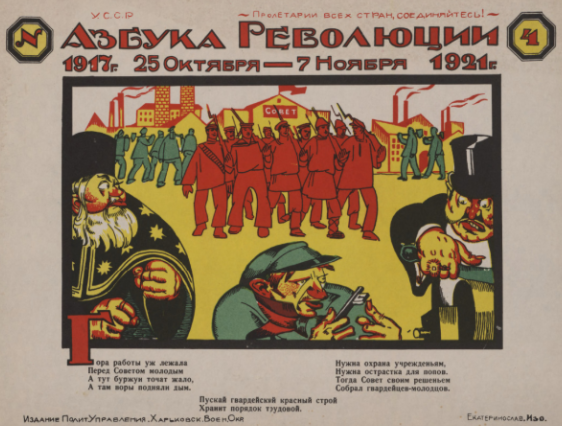

A capitalist-allied clergy can be found in early propaganda posters, such as the 1921 poster Revolution From A to Z by Adol’f Strakhov (Strakhov). In this piece, three figures are depicted as concerned by the presence of the communist-aligned Red Army guards: a bourgeois, a thief, and a priest (Strakhov). The accompanying caption in the poster makes it clear that the priest seeks protection from the bourgeois, who is sharpening a knife to use against the soldiers (Strakhov). Also of importance is the contrast in color between the supposed allies of capitalism and those of communism. The Red Army is fittingly depicted in a uniform shade of red, protecting red-colored factories (Strakhov). The usage of the Soviet Union’s eventual national color signifies unity and coalition that starkly contrasts the black adorned by the priest and the rich man, creating an in-group/out-group complex (Strakhov). Finally, observe the facial features of the supposed anti-communists, and compare them to those of the Red Army (Strakhov). While the poster utilizes forced perspective techniques by drawing the faces of the Red Army as smaller and less detailed, close observation of their faces reveals realistic, dignified features (Strakhov). Compare these faces to those of the priest, the thief, and the bourgeois, and it’s quite apparent that the faces in the foreground are supposed to appear inhumane, vicious, ugly, and potentially cowardly (Strakhov). The message of the poster is clearly both anti-religious and anti-capitalist, using individual caricatures to illustrate this.

Other 1920s propaganda posters focused on collective belief by employing recognizable religious symbols to depict religion as a tool of social manipulation for the rich. This allowed the illustrators to paint not just members of a religion in a negative light, but also a particular religion itself. Artist Dmitri Moor’s The Triumph of Christianity depicts a heavyset capitalist riding on a cross, holding reins that guide workers carrying the cross (Moor). These workers follow Jesus as a religious carrot on a capitalist’s stick despite the obvious signs of abuse and malnourishment on their skin and figures (Moor). The coloring choices for the poster are key to understanding its message. The workers carrying the cross appear in white, granting them the appearance of skeletons and a sense of foreboding (Moor). Meanwhile, the rich man, the cross, and Jesus are all colored in shining gold, which not only represents wealth and capital but also demonstrates that the three are in allegiance with each other against the laborers (Moor). Religion and capitalism are thus depicted as both enemies of the working class and friends of each other.

These posters played off the idea that priests used religion as a tool to suppress the working class and assist the ruling class. Robert King notes in his article “Religion and Communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe” that Karl Marx and many of his adherents “saw religion as a compensation to those who were deprived of happiness in this world and who therefore sought it in looking forward to better conditions in the life to come” (King 323). Simply put, religion was an excuse, a reason for people to put up with harsh working conditions. Though they would suffer now, there was no reason to complain as retribution and rewards would appear in the afterlife, a notion completely antithetical to the revolution. Considering the recency of the Soviet uprising against the upper class (which originated in the late 1910s), as well as the priority of communist economic systems in the new Soviet Union, it is quite understandable that the Party would utilize propaganda that highlighted a supposed marriage between religion and capitalism. The fear of capitalism in the hearts of communists caused a rapid, widespread introduction to anti-religious posters in the 1920s and would continue to be a common theme throughout future propaganda pieces until the end of the Cold War, though it would not always remain popular. However, these pieces provided the basic formula for future posters, depicting religion as purposefully and maliciously against the good of the Soviet Union.

An Age of Soviet Propaganda Against Selfish Priests

Around the time of World War II, a new argument for anti-religious movements arose. Bernard Pares, in his article “Yaroslavsky on Religion in Russia”, discusses a pamphlet by Emilian Yaroslavsky, President of the Union of Militant Godless, titled “On Religious Propaganda” (Pares 343). Pares writes that the Union of Militant Godless highlights “the hypocrisy of priests who, while promising to others the good things of heaven, take care to secure for themselves those of earth” (Pares 346). Yaroslavsky took issue with hypocritical actions by religious clergy. He not only argued against material goods, which priests hypocritically garnered, but even called out theft of opportunity by “corrupt priests who sought high office” (Pares 346). Yaroslavsky was not alone in his accusations, with many pointing to the alleged alliance between priests and capitalists as proof that there was something suspicious going on beneath the surface. In order to raise loyal Soviets, new propaganda posters were produced to exploit fears of religious hypocrisy.

One common means of demonstrating this supposed religious hypocrisy in anti-religious propaganda was to depict priests as failing to follow the advice and commands they granted to their congregations, such as in E. A. Shukaev’s We Came for 'the Holy Water'... poster (Shukaev). The work depicts two Soviet women approaching a church with bottles, hoping the priest will gift them holy water, likely to serve some medicinal purpose (Shukaev). The nun who greets them, however, informs the women that the priest is unavailable since he is receiving mineral water treatment at a resort (Shukaev). The mention of mineral water treatment in this poster implies that the priest is utilizing the mineral water for healing, as opposed to his own holy water (Shukaev). The colors within the work are quite limited: light blue and black (Shukaev). The light blue harkens to the image of water, and is present in both the bottles and some of the church’s decor, portraying the church as the provider of holy water (Shukaev). However, the dark colors of the church, especially through the doorway of the building, convey to the audience a distrust of the church’s capability to genuinely grant the life-giving water (Shukaev). Of interesting note is the facial expressions featured in the work: the nun appears with a smile on her face as she addresses the women, demonstrating that she is unfazed by the priest’s behavior (Shukaev). Meanwhile, the foremost woman who is depicted as older than her companion has a look of surprise (Shukaev). The older woman’s age and faithfulness to gathering holy water highlights the contrast between longtime religious believers and the hypocritical clergy betraying them (Shukaev). The state hoped to illustrate that if a priest did not trust in their own power, why should the public trust in it? This method planted doubts about the spiritual capabilities of priests, in contrast to the ideas of a manipulative religio-capitalist alliance shown in older propaganda pieces.

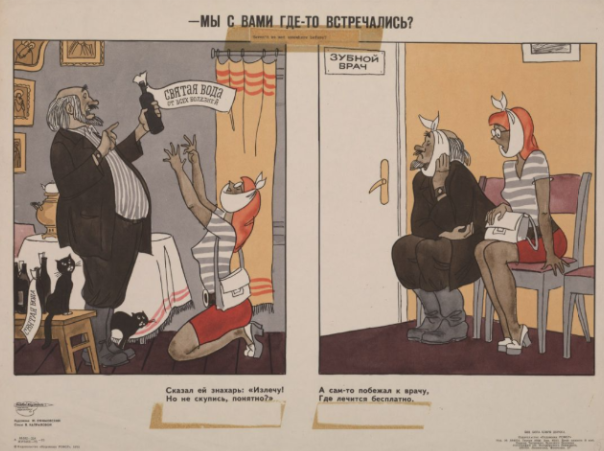

This idea of clerical hypocrisy even appeared in propaganda as late as 1975, as seen in Haven't We Met Somewhere Before? by Zhozef Efimovskiĭ (Efimovskiĭ). In the left frame of this poster, a religious healer of some kind (as denoted by the iconography in the background) is giving a young woman healing holy water to help with her toothache, with contextual clues making it obvious that he is demanding financial generosity in return (Efimovskiĭ). However, in the following frame, both the healer and the woman are depicted in the waiting room of a dentist in order to heal their toothaches (Efimovskiĭ). It is important to note that in the left frame, the healer had another bottle of holy water to heal himself with, and yet still needed the dentist, highlighting the hypocrisy in his spirituality (Efimovskiĭ). The dark colors associated with the healer and his cats pose a stark contrast to those of the woman (Efimovskiĭ). They highlight the superstitious man in a sinister light (Efimovskiĭ). The cats are also more telling than they seem since black cats are seen as a symbol of bad luck in many cultures due to their association with superstition (Efimovskiĭ). The fact that a healer would therefore own them links his alleged power to maligned superstition (Efimovskiĭ). As a final nail in this healer’s coffin, the text beneath the poster denotes that the healer is receiving his treatment at no cost, and is therefore hypocritical in how he manages his money since he is paying nothing for the visit when he commanded the young lady to be generous with her own money (Efimovskiĭ). Notice the young lady’s expression in both frames: in the left frame, she is excited and desperate for the holy water, while in the right frame, she is shocked by the healer’s presence (Efimovskiĭ). In contrast, the healer’s facial expression is nearly identical in both scenes, showing he is neither surprised by his own ailment nor ashamed of his poor appearance before a patient (Efimovskiĭ). The poster connects with its audience by highlighting that they suffer at the expense of a knowingly hypocritical and lying religious order (Efimovskiĭ).

Soviet anti-religious propaganda attempted to paint priests, clerics, and religious authorities in a light of hypocrisy. The reason why this hypocrisy was brought into the spotlight likely stemmed from World War II developments. In his article “Unholy Crusaders: The Wehrmacht and the Reestablishment of Soviet Churches during Operation Barbarossa,” David Harrisville writes about religious support for the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, stating that, “cognizant of Christian support for the invasion, Nazi leaders borrowed elements of religious rhetoric in their own propaganda” (Harrisville 648). This religious support, in direct opposition to the ideology of the Soviet Union during World War II, provided a legitimate fear of religion amongst the Soviets; a fascist approval of religion was more than enough to concern their Soviet opponents. Propaganda posters capitalized on this fear to limit the possibility of continued anti-Soviet religious institutions both at home and abroad. If churches in Nazi Germany backed violence and betrayal in opposition to traditional Christian values, what else were they hypocritical about? Perhaps even in a post-war era, they would continue allegedly anti-Soviet efforts. Soviet propagandists brought attention to more minute, everyday hypocrisies by clerics (such as healings and holy water) to direct fears toward larger, more dangerous falsehoods. If the clergy could be made out as liars, these lies would be in direct contrast to prevailing ideals that priests and nuns were holy people worthy of respect. It was believed that by erasing the image of a holy and respectable people, religion in the U.S.S.R. would crumble. After the war concluded, the depiction of religious canting continued in propaganda posters, peaking during the 1960s as the superiority of Soviet brotherhood was touted over religious division, before a technological focus overtook these trends. However, one final propaganda technique would eventually prevail. Propaganda had always bragged about the superiority of secular Soviets, but those supposed success stories weren’t prominent within posters. More often than not, propaganda focused on diminishing the Soviets’ opponents rather than uplifting ideal Soviet citizens. In a new era of scientific advancements, however, highlighting religious hypocrisy would demand that the Soviets produce proof of nonreligious superiority in the realm of science. Thus, propaganda would now boast the fulfillments of the Soviet Union not just in the world, but beyond.

An Age of Soviet Propaganda for Scientific People

As the Cold War raged on, resulting in a renowned nuclear arms race, a final propaganda theme rose into the limelight. The people needed to be assured of the state’s superiority on the grounds of scientific advancements. N. S. Timasheff writes in his 1955 article “The Anti-Religious Campaign in the Soviet Union” that state propaganda had begun to “[concentrate] on the irreconcilability of religion with science and communism” (Timasheff 331). Religion was viewed as an inferior ideology to atheism. It lacked intellect and factual support. Posters were supposed to illustrate that religion had no standing to begin with.

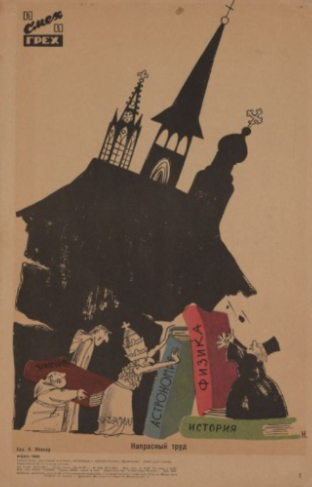

Some artists chose to illustrate religion’s contradictory approach to the academic world by highlighting how religious institutions were now suddenly accepting scientific findings. Examine the 1965 poster titled Wasted Efforts by Konstantin Nevler, which depicts four clergymen attempting to prop up a collapsing church building with books on various academic fields: astronomy, chemistry, history, and physics (Nevler). This conveys a clear message: religion is adopting academic disciplines as a life vest, a last-ditch effort to continue in the scientific age (Nevler). Consider also the different Christian denominations represented in the poster, with Roman Catholicism’s representative being the pope, Eastern Orthodoxy’s representative being a priest (possibly the Patriarch of Constantinople), and two additional men likely meant to represent Protestantism (Nevler). Coupled with the various steeples and spires of the church, drawing upon the architectural style of numerous Christian traditions, this poster argues that all Christian denominations are leeching off of scientific advancements solely because they can not stand in society without them (Nevler). Whereas many early anti-Christian posters solely targeted the Russian Orthodox Church, the importance of Roman Catholicism and Protestantism throughout the Western world (and especially in the United States) meant that the state had to issue a response against such faith traditions as well. Thus, beginning in the 1960s, the Soviets expanded their anti-Christian propaganda to discourage all the Christian denominations. The color choices implemented in the work also highlight the idea that the value of the churches pale in comparison to secular science, with religious figures being depicted in a dreary black and white, while the academic literature is depicted in vibrant and lively colors meant to attract the viewer’s attention in an otherwise bleak illustration (Nevler). Manipulating citizens into viewing religion as a dark and crumbling institution that merely grasped at science for its own benefit was a priority of the state.

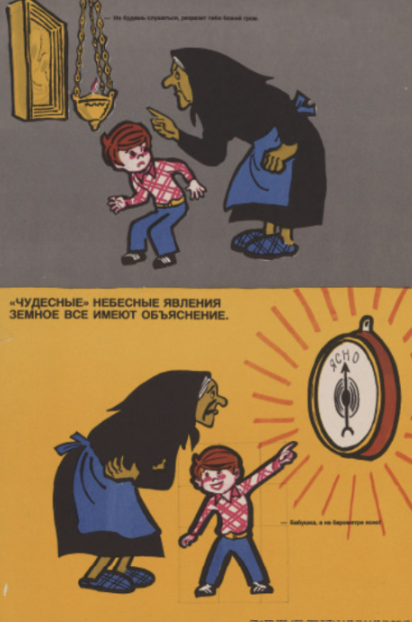

Other propaganda posters focused on religious beliefs and superstitions being simply untrue in light of scientific advancements. This thematic choice is seen in I︠U︡riĭ Cherepanov’s poster All “Miraculous” Celestial Events Have Mundane Explanations, as in the top frame, a grandmother is warning her grandson of divine retribution via thunder if he does not obey (Cherepanov). In the frame underneath, the grandson informs his grandmother that thunder is unlikely due to readings on the barometer (a weather instrument), which makes a mockery of his grandmother’s religious claim (Cherepanov). This work highlights the supposed utilization of fear in religion. The stern and worried grandmother utters a warning, while the supposed freedom found in scientific atheism is demonstrated by the joy on the grandson’s face (Cherepanov). Emphasizing generational conflict plays into the idea that secularism is modern and civilized when compared to the backward views of elders. Such conflict is poetically depicted as only resolvable through deconversion; only after both generations adopt non-belief can they be brought to unity (Cherepanov). Color choices once again greatly contribute to this message (Cherepanov). The grandmother is dressed in dark, old-fashioned clothing as she gives her ominous warning against a black backdrop (Cherepanov). Meanwhile, the grandson is wearing colorful modernized clothes and proclaims his belief in science amidst a bright gold backdrop (Cherepanov). Note the lines protruding from the barometer as rays of brilliance that likely draw inspiration from halos and rays of glory in religious iconography (Cherepanov). Ultimately, every aspect of the poster, as well as similarly produced propaganda pieces, worked to dismiss religion in such a meticulous manner (Cherepanov).

While the concept of scientific superiority had existed as a theme in posters since the conception of Soviet antireligious propaganda, it was not frequently used until the Space Race, though it would later spike again during the 1980s. Upon the conception of the Soviet Union, a sense of Soviet identity was built around the idea that the Soviet Union represented a modern and progressive way of life, having done away with several archaic institutions. Just as the economic systems of the previous government had been overhauled, the Soviet Union strongly advocated for the overhaul of education and engineering careers. Support for progress and reason became the Soviet dream in place of religion and tradition. This advocacy spiked during the Space Race, as STEM fields rose to great prominence in both the United States and the Soviet Union, with both powers attempting to weaponize themselves beyond Earth’s boundaries. As such, scientific knowledge now served as a resource for success in the Space Race, a resource that many Soviet state officials believed should not be hindered by religion in any capacity. While it is difficult to pinpoint whether most of these officials genuinely believed in religion’s lack of scientific developments or if they simply did not want to appear as if the atheists had lost an intellectual battle against the Americans (since many came to associate Americans with devout Christians), its uncontested that the state pushed for religion to be viewed as backward, archaic, and intellectually inaccurate. Gustav Wetter states in his article “Ideology and Science in the Soviet Union Recent Developments,” which examines Soviet scientific views on religion, that “religion stands or falls with the geocentric system” (Wetter 590). This statement alludes to the geocentric model of the galaxy that was originally propagated by many religious authorities until scientific advancements in the seventeenth century resulted in a heliocentric understanding. Advances such as these were utilized to convey the non-necessity of religion advocated by Soviet atheists. While the Space Race first brought this thematic concept into the spotlight, it was heavily reintroduced again during the 1980s, amidst the Americans’ Strategic Defense Initiative and the Soviets’ increased missile armament, both of which emphasized scientific advancements similar to those called for during the Space Race. This theme would continue to be incorporated into Soviet anti-religious propaganda posters until the fall of the U.S.S.R. in 1991.

Conclusion

The expansive history of Soviet anti-religious propaganda posters features a wide variety of thematic choices and focuses. However, when seeking a specific answer as to why they developed over time, an examination of historical events reveals that the posters developed according to the ever-changing cultural climate of the Soviet Union. This paper demonstrates how Soviet posters evolved in response to political and social developments, specifically addressing religious leaders aligned with capitalism, hypocrisy among clergymen, and scientific superiority under atheism. These thematic choices were orchestrated in line with the political world of the Soviet Union, a world of shifting methodologies which therefore required ever-changing propaganda pieces.

Understanding these thematic trends in Soviet anti-religious propaganda posters can assist with assessing the Soviet state’s priorities. While the three propaganda themes may not be entirely distinct (you will not find one theme being discontinued before a new one is adopted, and you will find the blending of themes), it is clear that each thematic choice had a period of prominence. These periods align with the shifting political priorities of the Soviet Union, as the propaganda choices of the nation matched its concerns. Historians can thus utilize this timeline to track key political focuses of the U.S.S.R. over time, from economic concerns to post-war fears and scientific aspirations.

This research poses some new questions for historians. For example, how did Soviet citizens, religious or not, react to each propaganda theme? Some may have been more convincing to the citizens than others, and therefore the propaganda shape would shape the cultural developments that would one day produce new propaganda of a different theme. Another question that may be posed is: How regional were the thematic choices of anti-religious propaganda posters throughout the Soviet Union? The Soviet Union was a heavily centralized global power. However, it spanned half a continent and retained fifteen different republics. While this research has presented a birdseye view of Soviet Union propaganda production, it is very possible, and even expected, that some differences in propaganda pieces may occur in different locations. These differences may go deeper than simple artistic style changes, perhaps even on a thematic level.

It is quite clear that the Soviet Union organized the creation of its propaganda posters according to the cultural focus at the time of their production. Whether it was aligning clerics with capitalists, saints with scam artists, or religion with unintelligence, these focuses became the themes of propaganda posters throughout the Soviet Union. Each political shift or cultural change prompted the state to capitalize on new themes for its propaganda. The propaganda was perceived by the state as needing adjustments to succeed. Soviet citizens were raised under a patriotic, pro-worker, anti-religious state, and their proud comrades would already indoctrinate them into recognizing the themes presented within the posters, whatever they may be. The Soviet Union's centralized issuing of such propaganda represented a frequent change of heart regarding psychological battle tactics against religion. And with each change of heart, there was a necessitated change of art.

Edited by Emma Stanislavsky (Barnard College '28) & Julia Hunt (Columbia College '27)

Works Cited

Primary Sources

Cherepanov, I︠U︡riĭ. All “Miraculous” Celestial Events Have Mundane Explanations. 1984, poster. Keston Center - Keston Digital Archive. https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/all-miraculous-celestial-events-have-mundane-explanations./1064070

Efimovskiĭ, Zhozef. Haven’t We Met Somewhere Before?. 1975, poster. Keston Center - Keston Digital Archive. https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/havent-we-met-somewhere-before/1064130

Marx, Karl. "Introduction”. A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right. Unpublished manuscript, 2009.

Moor, Dmitri. The Triumph of Christianity. 1923, poster. Merrill C. Berman Collection. https://mcbcollection.com/early-soviet-anti-religious-propaganda

Nevler, Konstantin. Wasted Efforts. 1965, poster. Keston Center - Keston Digital Archive. https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/waisted-efforts/1064109

Review of “Draft of a Decree of the Party of Workers and Peasants Central Committee’s Plenary Session on the Issues of the Party Program’s Paragraph Thirteen Violation and on the Organization of Anti-Religious Propaganda”. 1921, p. 251. Keston Center - Keston Digital Archive. https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/draft-of-a-decree-of-the-party-of-workers-and-peasants-central-committees-plenary-session-on-the-issues-of-the-party-programs-paragraph-13-violation-and-on-the-organization-of-anti-religious-propaganda./1743778

Shukaev, E. A. We Came for 'the Holy Water'.... 1965, poster. Keston Center - Keston Digital Archive. https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/we-came-for-the-holy-water.../1064091

Strakhov, Adol’f. Revolution From A to Z. 1921, poster. Keston Center - Keston Digital Archive. https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/revolution-from-a-to-z/1064111

Secondary Sources

Andrew, Denny. “Soviet Propaganda.” The Military Engineer, vol. 43, no. 294, 1951, pp. 259-262. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44561310

Curtiss, John, and Alex Inkeles. “Marxism in the U.S.S.R.—The Recent Revival.” Political Science Quarterly, vol. 61, no. 3, 1946, pp. 349-364. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2144639

Grossman, Joan. “Khrushchev's Anti-Religious Policy and the Campaign of 1954.” Soviet Studies, vol. 24, no. 3, 1973, pp. 374-386. https://www.jstor.org/stable/150643

Grossman, Joan. “Leadership of Antireligious Propaganda in the Soviet Union.” Studies in Soviet Thought, vol. 12, no. 3, 1972, pp. 213-230. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20098504?seq=4

Harrisville, David. “Unholy Crusaders: The Wehrmacht and the Reestablishment of Soviet Churches During Operation Barbarossa.” Central European History, vol. 52, no. 4, 2019, pp. 620-249. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26870259

King, Robert. “Religion and Communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.” Brigham Young University Studies, vol. 15, no. 3, 1975, pp. 323-347. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43040567

Pares, Bernard. “Yaroslavsky on Religion in Russia.” The Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 16, no. 47, 1938, pp. 342-355. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4203368

Powell, David. “The Effectiveness of Soviet Anti-Religious Propaganda.” The Public Opinion Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 3, 1967, pp. 366-380. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2747392

Timasheff, N. S. “The Anti-Religious Campaign in the Soviet Union.” The Review of Politics, vol. 17, no. 3, 1955, pp. 329-344. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1404796

Wetter, Gustav. “Ideology and Science in the Soviet Union Recent Developments.” Daedalus, vol. 89, no. 3, 1960, pp. 581-603. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20026600